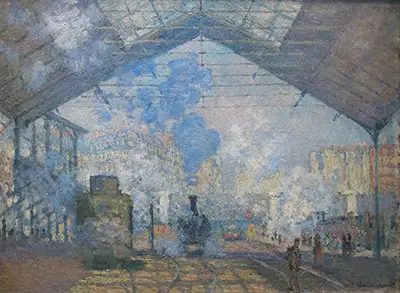

However, Monet was one of many contemporary artists – such as Gustave Caillebotte and Georges Seurat – whose paintings are a response to the changes in Parisian life and the growth of the suburbs and towns around the capital: a change made possible by the expansion of the railways. Saint-Lazare was a station that Monet would have known well. From here, trains would wind their way out of the Ile de France, across rivers and fields, to the coastal resorts evoked by Proust, and to Monet’s home in rural Normandy, near the Epte and the Seine. In contrast to his visions of garden and countryside, Monet's response to the station scene – or rather ‘responses’, for he returned to the subject a number of times – is one of energy and urban modernity.

Under the glass roof of the engine shed, we see an impression of the movement of people and the dormant power of the locomotives. It is a painting with an immediate and still recognisable sense of place: the coming and going of a busy city, and in the background, a hint of the characteristic warm stone and pale grey roofs of the post-Haussmann Parisian skyline, set against a brilliant blue. It is difficult to recapture, at this distance of time, the excitement that the railways generated among almost all areas of society. Flaubert’s Dictionary of Received Ideas makes a joke of it: marvelling at this wonder of the age had already become a cliché of conversation from the salon to the café. But many others were in earnest. Emile Zola responded admiringly to Monet’s work, seeing it as an apt response to the artist’s new role in modern life.

“Monet,” he wrote “is able to transform what is usually a dirty and gritty place into a peaceful and beautiful scene”, comparing the approach to artists of earlier eras looking for the sublime in the natural world around them. Other painters took up the challenge too. Caillebotte and Edouard Manet, who both lived nearby at one time, included trains and the infrastructure of the railway in their work. Nor was it uniquely a national fascination. In far-away Prague, a nine-year-old Antonin Dvořák was captivated by the heat, smell and sound of the steam locomotives which served the new railway line to his capital city – many have claimed to hear their power and rhythm in his music. Later he was to say: "I would have given all of my symphonies to have invented the locomotive."

The busy station is an archetypal impressionist subject in other ways too. The ephemeral and changing effects of steam offered brilliant possibilities for an artist captivated by the qualities of light and colour. Shafts of angled sunshine from the roof and across the open platform allow Monet the scope to demonstrate his subtlety of eye and personal confidence of technique. It also reveals the Impressionists’ debt, in vision and treatment of the subject, to Turner, the great English exponent of painting in light. Rain, Steam, and Speed - The Great Western Railway (1844) - in London’s National Gallery, with one of Monet’s paintings of the Gare Saint-Lazare – conveys much of the same fascination with the impression and moment of the experience.