This painting is a presage of Monet's Water Lilies series, over two hundred paintings he executed between 1916 and 1922 of the effects of changing seasons upon the pond of his house at Giverny, for example, Water-Lily Pond and Weeping Willow (1916-19).

These deceptively simple paintings have a long, artistic heritage. From the landscape images upon the walls of the House of Livia (c. 1 AD) in Pompeii, down through the landscapes of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Rocks on the Mediterranean Coast encompasses several milestones in the history of art.

From medieval times to the end of the Renaissance, the majority of artists’ commissions were for religious paintings, and mythical scenes and portraits for wealthy people. However, the sea and landscape painting became fashionable in the secular world of Dutch art. (See Michelangelo paintings and Da Vinci paintings plus Masaccio for examples of this.)

The seascape, in particular, flourished during the 1600’s when Dutch artists such as Ludolf Bakhuizen (1630-1708) painted realistic renderings of ships and boats at sea, accurate in every detail from the structure of the crafts to the foam crests on the water, for example, Seascape and Fishing Boats, (1708).

By the 1800’s, the fashion for realism had declined, partly because of the invention of the camera. Patrons sought out allegorical landscapes, such as Dejeuner Sur L’Herbe (1862-3) by Edouard Manet.

Earlier in the nineteenth century, Johan Wolfgang van Goethe had published his book, Theory of Colours, and artists had embraced the philosophy that what the viewer remembers about an image is as significant as what he actually sees as he looks at it. Colour, in particular, leaves memorable after-impressions in the mind and in his book, Goethe painstakingly charts hundreds of these impressions.

It was from this philosophy that the style of painting we call impressionism, grew. Artist J.M.W. Turner's Snow Storm: Steam-Boat off a Harbour's Mouth (1842) demonstrates the transition from naturalistic depiction to paintings that express the inner yearnings of the artist.

Meanwhile, paint technology had advanced throughout the 1800's. Many shades and hues of paint were available in squeezable metal tubes, and the flat ferrule brush came into being. No longer did the artist need to build his imagery in fine strokes from the “point” of a round ferrule brush, almost like writing with a pen.

With the ferrule flattened, the brush hairs gave him a new power over the impressions that he could create. Commercial artists painted land and seascape impressions for paying patrons at tourist resorts very quickly, and in very bright colours. In contrast to this “commercial” painting, Rocks on the Mediterranean Coast is a thoughtful and painstaking composition.

Other key exponents of colour would follow laterin the 20th century, inspired by the work of Monet and other members of the impressionist movement. Famous examples of this include Guernica, Castle and Sun and The Son of Man.

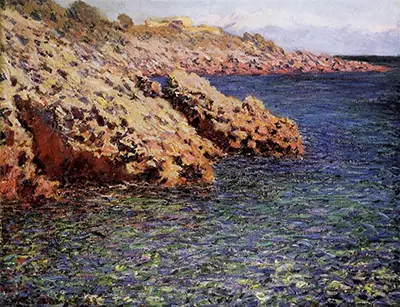

The land and sea elements are imbued with a perceptible energy, originating from Monet's understanding of complementary colour. He has placed the colours opposite each other on the colour wheel, purple and orange, red and green, and blue and yellow, against each other in the painting.

The bright orange and yellow rock juts dramatically from the purple-blue sea. Composed of red and blue strokes, the ocean appears purple at a glance, the same hue that results when these colours are mixed physically. The dark blue of the sea behind the rock creates an impression of distance, while the flecks of green algae in the foreground refer to Monet's paintings of water lilies.

What is most significant is the connection between the land and the sea, the way the rock spreads across the water like a sleepy animal reclining in the sunshine. Overall, Rocks on the Mediterranean Coast is a triumph of technique and technology, colour and beauty.